‘With free software on the Internet and apps, creating a deepfake video can take 3 to 5 minutes. Anyone can make these videos.’

When ChatGPT made headlines earlier this year, it marked how people could use generative artificial intelligence (AI) in their daily lives.

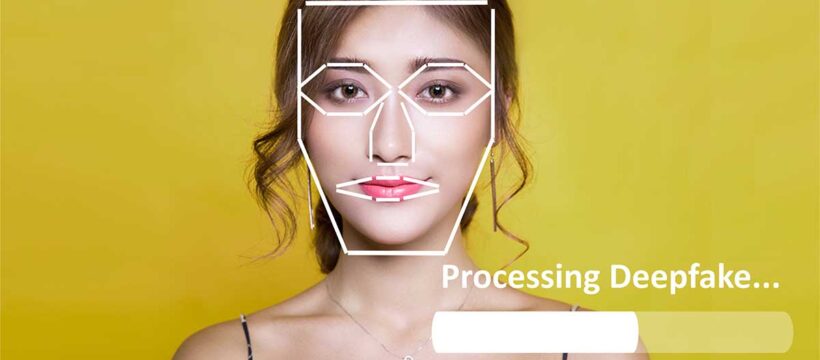

Headlines now speak of how AI is being used for ‘deepfakes’, or the manipulation of voice and facial data.

The technology has been around since 2017, but what has shocked India is how easily it can be used to spread disinformation, harass or blackmail people.

Public uproar began last month when a fake video of actor Rashmika Mandanna surfaced. Her picture was morphed over that of British Indian social media personality Zara Patel.

Fake videos of actors Katrina Kaif and Kajol followed soon. Earlier, in July, Tamil Nadu Minister Palanivel Thiagarajan alleged that a fake audio recording of him had been made public.

Deepfakes could be a hazard in a country heading to general elections next year and with a growing Internet user base. ‘Deepfake is a big concern. AI has to be safe for the public,’ said Prime Minister Narendra D Modi last month.

Faking it is easy

“Two-three years ago creating a deepfake video would take 15-20 days, but with free software on the Internet and apps, this has been crunched to three to five minutes. Absolutely anyone can make these videos,” said Divyendra Singh Jadoun, founder of The Indian Deepfaker, which uses the technology for advertisements and marketing and works with firms like Tata Tea, Wakefit, and with political parties to send personalised messages.

Deepfakes comprise just 0.09 per cent of all cybercrimes, but are alarming because they enable lifelike impersonations, said a recent study by the Future Crime Research Foundation (FCRF).

“Despite its relatively small presence, the impact of deepfake crimes is profound, warranting proactive measures to safeguard individuals and maintain digital trust,” said Shashank Shekhar of FCRF.

Deepfake online content increased by 900 per cent between 2019 and 2020, according to a blog post by the World Economic Forum. Researchers predict that ‘as much as 90 per cent of online content may be synthetically generated by 2026’.

Last year, as many as 66 per cent of cybersecurity professionals experienced deepfake attacks on their organisations.

This year, 26 per cent of small and 38 per cent of large companies worldwide have experienced deepfake fraud resulting in losses of up to $480,000, said the WEF blog post.

Jadoun realised the impact a deepfake can have when he once created such a video of actor Salman Khan wishing people on Eid.

‘It was a very low quality video and I just uploaded it on Moj [an online video platform]. Within a few days I received a total of 400 comments, of which 300 believed that it was the real video. This was scary,’ he said.

The fightback

Information Technology Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said the government ‘within a short time’ will have a new set of regulations for deepfakes.

The new rules will penalise the creator of deepfakes and the platforms hosting such content.

Rajeev Chandrasekhar, minister of state for electronics and information technology, said his ministry would develop a platform where users could be notified about rule violations by social media platforms.

Meanwhile, social media players too are fighting back. In the second half of 2023, YouTube removed more than 78,000 videos that violated its manipulated content policies. It also removed 963,000 videos for spam, deceptive practices and scam.

The Google-owned video platform will over the months introduce updates that inform viewers when the content they are viewing is synthetic. It will ask creators to disclose when they have altered or used synthetic content that appears realistic, including by using AI tools.

‘Creators who consistently choose not to disclose this information may be subject to content removal, suspension from the YouTube Partner Program, or other penalties,’ said the platform in a blog post.

YouTube will make it possible to request the removal of AI-generated or other synthetic or altered content that simulates an identifiable individual, including their face or voice.

Google is investing in detection tools like SynthID, which identifies and watermarks AI-generated images.

In May, Google said it was making progress in building tools to detect synthetic audio.

Google’s ‘About this Image’ feature gives context to evaluate online visuals. It tells users when an image was first indexed by Google, where it may have first appeared, and where else it has been seen online.

Meta, which owns Instagram and Facebook, has announced that a new policy from next year will require advertisers to disclose digital alteration of content on its platforms.

Advertisers will have to disclose whenever a social issue, electoral, or political ad contains a ‘photorealistic’ image or video, or audio digitally created or altered to depict a real person.

Pictures and videos depicting a real person or event that did not happen, or altered footage of a real and genuine event will also have to be reported on Meta platforms.

‘We’re announcing a new policy to help people understand when a social issue, election, or political advertisement on Facebook or Instagram has been digitally created or altered, including through the use of AI,’ said the company.

Will governments and companies be able to contain deepfakes?

Regulations against the misuse of deepfake technology are uneven and vary in jurisdictions, said Kumar Ritesh, founder and chief executive officer of Cyfirma, a cybersecurity firm.

The government should invest in public awareness campaigns.

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article